Blue Carbon and Urban Resilience

juin 22, 2022 — Uncategorized

As coastal cities around the world determine their climate mitigation and adaptation plans, an important nature-based solution must be considered: Blue Carbon. Much has been written about this topic in the academic and NGO spheres; however, its recent introduction into the mainstream conversation reflects its growing importance in city planning, financing, and operations. This is due to blue carbon’s environmental, economic, and social benefits, and the associated risks if ignored.

Blue Carbon and Why it Matters

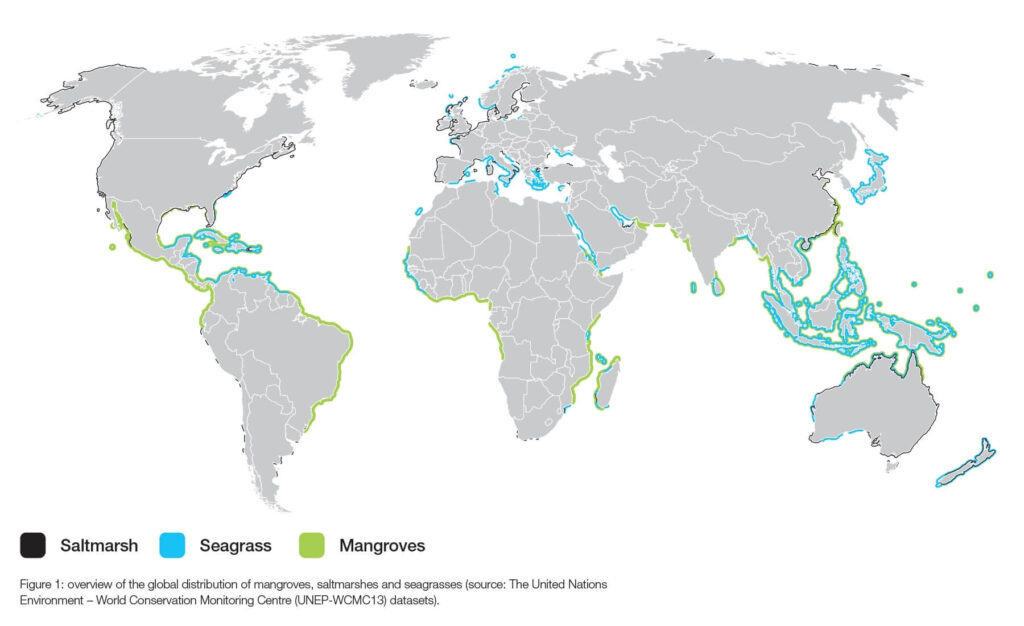

Blue carbon is carbon that’s captured and stored in ocean and coastal systems, specifically in mangrove forests, sea grasses, and tidal marshes. Over 80% of global carbon is cycled through the ocean, which makes it critically important to climate change.1 Blue carbon accounts for over 50% of carbon stored in ocean sediments, and could absorb up to 1.4B tons of emissions annually by 2050.2 Mangroves and salt marshes remove atmospheric carbon at a rate 10 times greater than tropical forests, while seagrasses sequester carbon 35 times faster than rainforests, storing it for millennia versus decades.1,2

Blue carbon ecosystems are widespread, covering almost 50 million hectares on every continent except Antarctica.3 This includes tropical coastlines around the world, as well as temperate and subpolar areas such as Port Phillip Bay in Melbourne Australia, the Bay of Fundy in Canada, and Scotland where blue carbon sequesters about three times as much carbon a year than all of its forests combined.4

Aside from their key role in the global carbon cycle, blue carbon ecosystems also provide local communities with a variety of economic and cultural benefits. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the stunning beauty of these ecosystems as well. When I think of marshes, my mind wanders to the densely vegetated Chesapeake Bay coastline of my home state of Virginia, which is teaming with life. Mangroves and seagrass remind me of my favorite scuba diving site, a place in the Milne Bay area of Papua New Guinea called “Observation Point.” It was named by my mentor Dr. Eugenie Clark (“The Shark Lady”) as its sandy outshoot was the perfect place to study the sand diver fish Trichonotus. Aside from a fringing coral reef, the area also included seagrass meadows with dancing shrimpfish and a vibrant mangrove forest inhabited by enormous bright orange seahorses. I encourage everyone to visit blue carbon systems if they have the opportunity, and to view their majesty above and below the water.

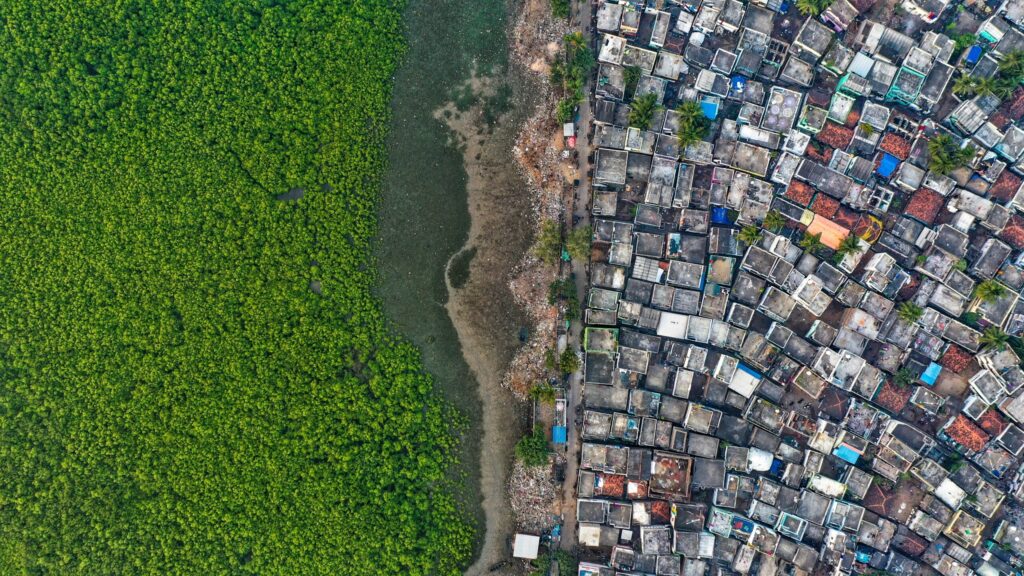

Unfortunately, places like Observation Point are becoming increasingly rare since blue carbon systems are disappearing at an alarming rate, especially in urbanizing areas. Already the world has lost 30% of its seagrasses and 50% of its mangroves and tidal marshes.1,3 Each year humanity’s destruction of coastal wetlands releases 450 million metric tons of CO2, the equivalent of 97 million cars.3

Blue Carbon and Cities

Currently 2.4 billion people, about 40% of the world’s population, live within 100km of the coast.5 About a billion of these people are within 100km of a seagrass meadow and 100 million within 10km of significant mangrove systems.6 These numbers will increase significantly in the coming decades as billions of additional urbanites join the planet, primarily in tropical and sub-tropical areas. The timing couldn’t be worse, as climate-related risks will continue to increase dramatically.

As more and more coastal cities develop and implement resiliency plans, and practitioners and policy makers start planning for a changing planet, the following blue carbon factors should be considered:

Environmental

Along with climate benefits, blue carbon systems have numerous other natural benefits: increasing coastal resilience to storms by absorbing storm surge, controlling erosion, reducing the release of pollutants into coastal waterways, and providing critical habitats.7

Economic

Blue carbon systems serve as the backbone of many industries. Seagrasses alone create a nursery habitat for almost one fifth of the world’s largest fisheries, and salt marshes provide food, refuge, and habitat for over 75% of U.S. fisheries.6,7 It is estimated that annually mangroves are worth $33,000-57,000 per hectare and seagrasses are worth almost $30,000 per hectare in ecosystem services.6,7 These systems not only protect fish and other animals, but people and property as well. Specific to urban areas, mangroves protect 15 million people a year from flooding and reduce property damage by more than $65 billion.8 The first 100 meters of mangroves are able to lower wave heights by as much as 66%, an important incentive for cities to maintain or restore these systems.9 Financial institutions like AXA XL are now looking at opportunities to insure mangroves to build resiliency, similar to novel programs to insure coral reefs.9

Healthy blue carbon systems save cities money. In the Galveston Bay of Texas, salt marshes reduce the demand on municipal wastewater treatment by mitigating the release of pollutants into coastal waterways, saving an estimated $124 million.7 The Economist notes that building a sea wall costs about $20 million, but restoring mangroves to protect the same area costs only about $23,000 in the Caribbean and $45,000 in Florida.10 On a global scale, the Global Commission on Adaptation estimates that protecting and restoring mangroves globally would cost less than $100 billion but would create $1 trillion in net benefits by 2030.11

Tourism jobs and businesses also are supported by blue carbon systems. In Singapore, visitors kayak through the mangrove forests of Pulau Ubin and in Abu Dhabi walk the trails of the Mangrove Park on Jubail Island. A recent study identified 3945 mangrove “attractions” in 93 countries and territories.12 Historically, hotels removed sea grasses believing they were unsightly, but research shows this causes higher turbidity and loss of biomass.13 A great example of a hotel embracing sea grasses to enhance the tourism experience is the Six Senses Laamu in the Maldives. Not only are they conserving their own sea grasses, but they helped develop a National Seagrass Monitoring Protocol and persuaded 37 other resorts to protect their seagrasses.14

Society

Blue carbon systems have a variety of positive impacts on people and communities too. This includes core needs like income, food security, and access to clean water, as well as culture and recreation. Also, there are issues related to equity, property rights, and maintaining traditional practices.

Academia is starting to synthesize the importance of blue carbon and communities, particularly for low and middle-income countries. Blue carbon projects are showing positive results in supporting community development projects like the Vanga Blue Forest in Kenya, where restoring and protecting almost 500 hectares of mangroves created social and economic benefits for the local community.17 A project to protect coastal areas in Indonesia that stopped 13 million metric tons of blue carbon from being released into the atmosphere amounted to $540 million in social welfare benefits.18

A recent article in the journal Ambio details how blue carbon frameworks for just and sustainability community engagement are emerging. This includes The Commonwealth Blue Charter and the Blue Carbon Code of Conduct, which acknowledge the importance of community rights and participation, as well as a “unity of purpose amongst the Blue Carbon community in learning from mistakes made in terrestrial ecosystems.”17 And a 2021 Frontiers in Climate article created a framework for operationalizing climate-just ocean commitments.

In places like New York City where funding is more abundant and blue carbon ecosystems have been degraded over centuries, developers are seeing the value in blue carbon restoration as part of their projects. The River Ring apartment high-rises in Brooklyn are being designed to include tidal pools and salt marshes while across the city the Rockaways, Arverne East will include a 35-acre restored beachfront and nature preserve on a site that used to be an abandoned parking lot.20 It’s a win-win for all involved: residents gain health benefits from access to outdoor spaces and developers see the value of their projects increase up to 20% while more easily earning community support and access zoning incentives.20. Bonnie Campbell from Two Trees, the developer of River Ring, told The New York Times: “One thing we heard over and over when we did stakeholder outreach with neighbors was the value in getting back to nature, feeling like you’re somewhere other than New York City, and feeling like you’re connected to the water.”

Blue Carbon Markets

In recent years the concept of blue carbon markets has gained steam worldwide. The Economist describes these as ecosystem restoration projects that generate ‘credits’ based on tonnes of carbon captured and stored. Those credits are then sold to buyers looking to offset their own carbon emissions.15 The market is still in its infancy, with demand outstripping supply. Their added appeal is due to improving adaptation and resilience, positive social impacts in vulnerable communities, and the potential to measure their impact.15 This is being reflected in real world case studies, such as the Mikoko Pamoja project in Kenya and Vida Manglar in Colombia. The Bahamas has identified $300 million worth of assets that could be offered on the voluntary carbon market. Not only does this incentivize conservation, but also it could offset future costs: almost half of the country’s existing $10 billion debt is connected to past damage from hurricanes and climate change.16

Similar to other offsets, blue carbon projects are contingent on the quality of the credits offered, how they are managed long-term, and community engagement. Perhaps the biggest challenge ahead is supply, as my friend and colleague Dr. Carlos Duarte told the Economist, “Financial resources for blue-carbon resources are growing rapidly, yet we don’t see a supply of projects that matches these funds.”10

One solution is determining how to market blue carbon, which is the topic of a new paper co-authored by Dr. Duarte and a team of transdisciplinary experts titled Operationalizing Marketable Blue Carbon. Blue carbon markets and nature-based climate solutions were recently outlined by McKinsey & Company too in their report Blue Carbon: The potential of coastal and oceanic climate action.

A Resilient Blue Future

Clearly, conserving and restoring blue carbon systems provides a variety of benefits to coastal cities, increasing environmental, social, economic, and built space resiliency. Inland cities should also consider their downstream impacts on these valuable and precious ecosystems.

I am hopeful that we’ll see city planners and managers increasingly embrace blue carbon strategies, like the Port of San Diego that is studying eelgrass’ ability to sequester carbon or the blue carbon credit initiatives underway in Fukuoka and Yokohama, Japan.

Countries are starting to embrace blue carbon as well, with 43 of 113 including it in their greenhouse gas inventories (“NDCs”) submitted at COP26. That number should expand this year, as described by Kristian Teleki of World Resources Institute: “Blue carbon is going to grow exponentially in the next 12–18 months; I would expect to see it featured highly at COP27. Without a doubt, people are waking up to the huge opportunity that the ocean presents to solve climate change, food security and poverty.”15

Our urban future depends on healthy and thriving blue carbon ecosystems. We have the tools and knowledge to protect and restore these amazing ecosystems. Now is the time for cities and communities to integrate blue carbon in their resilience plans.

Want to Learn More?

Check Out These Resources:

Blue Carbon Lab

International Partnership for Blue Carbon

Mapping Ocean Wealth

Ocean & Climate Platform

The Blue Carbon Initiative

Sources

1. The Blue Carbon Initiative. (n.d.). https://www.thebluecarboninitiative.org

2. McVeigh, Karen. (2021). Blue carbon: the hidden CO2 sink that pioneers say could save the planet. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/04/can-blue-carbon-make-offsetting-work-these-pioneers-think-so

3. Broom, Douglas. (2021). These blue carbon ecosystems could slow climate change. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/11/blue-carbon-cut-emissions-by-fifth/

4. McVeigh, Karen. (2021). The problem with blue carbon: can seagrass be replanted…by hand? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/05/seagrass-meadows-could-turn-tide-of-climate-crisis-aoe

5. The Ocean Conference. (2017). Factsheet: People and Oceans. United Nations. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Ocean-fact-sheet-package.pdf

6. UNEP. (n.d). Why protecting & restoring blue carbon ecosystems matters. https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/oceans-seas/what-we-do/protecting-restoring-blue-carbon-ecosystems/why-protecting

7. PEW. (2021). Coastal ‘Blue Carbon’: An Important Tool for Combating Climate Change. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2021/09/coastal-blue-carbon-an-important-tool-for-combating-climate-change

8. Sustainable Tourism International. (n.d.). What is Blue Carbon and Why Does it Matter? https://sustainabletravel.org/what-is-blue-carbon/

9. Cunliffe, C. (2020). Mangrove insurance-opportunities to build resilience in the Caribbean. AXA XL. https://axaxl.com/fast-fast-forward/articles/lets-talk-protecting-and-restoring-mangroves

10. World Ocean Initiative. (2021). How to scale up blue-carbon projects. The Economist. https://ocean.economist.com/blue-finance/articles/how-to-scale-up-blue-carbon-projects

11. Billecocq and Vegh. (2021). The business case for investing in resilient coastal ecoystems. UNFCCC. https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/the-business-case-for-investing-in-resilient-coastal-ecosystems/

12. Spalding and Parrett. (2019). Global patterns in mangrove recreation and tourism. Marine Policy. DOI: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103540

13. Daby, D. (2003). Effects of seagrass bed removal for tourism purposes in a Mauritian bay. Environmental Pollution. Volume 125, Issue 3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0269-7491(03)00125-8

14. Maldives Underwater Initiative by Six Senses Laamu. (n.d.). https://www.maldivesunderwaterinitiative.com/seagrass-conservation

15. World Ocean Initiative. (2022). Are blue carbon markets becoming mainstream? The Economist. https://ocean.economist.com/blue-finance/articles/are-blue-carbon-markets-becoming-mainstream

16. Wyss, J. (2022). The Bahamas Plans to Sell ‘Blue’ Carbon Credits in 2022, PM says. Bloomberg. https://axaxl.com/fast-fast-forward/articles/lets-talk-protecting-and-restoring-mangroves

17. Dencer-Brown et al. (2022). Integrating blue: How do we make nationally determined contributions work for both blue carbon and local coastal communities? Ambio. DOI: 10.1007/s13280-022-01723-1.

18. Hilmi et al. (2021). The Role of Blue Carbon in Climate Change Mitigation and Carbon Stock Conservation. Frontiers in Climate. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2021.710546/full

19. Reiter et al. (2021). A Framework for Operationalizing Climate-Just Ocean Commitments Under the Paris Agreement. Frontiers in Climate. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fclim.2021.724065/full

20. Sisson, P. (2022). The Next Level in Sustainability: Nature Restoration. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/15/business/developers-nature-restoration.html?searchResultPosition=1