Bogotá, Colombia | Wellbeing Cities Winner 2021

mai 7, 2021 — Highlight, Programmes

Bogotá, Colombia

Wellbeing Cities Winner

ABOUT

“Our mandate is to make Bogotá a caring, inclusive, sustainable city, where quality and relevant education is the main driver for social and economic transformation.” During 2020 Bogotá has focused its efforts on dealing with the pandemic to ensure the well-being of its citizens and also to promote a green economic recovery.

We are promoting a new social and environmental contract, that focuses on closing inequality gaps, prioritizing population groups that have traditionally been the most vulnerable: women, poor households, and youngsters, and accelerating the implementation of SDG’s, to make Bogotá a more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable city.

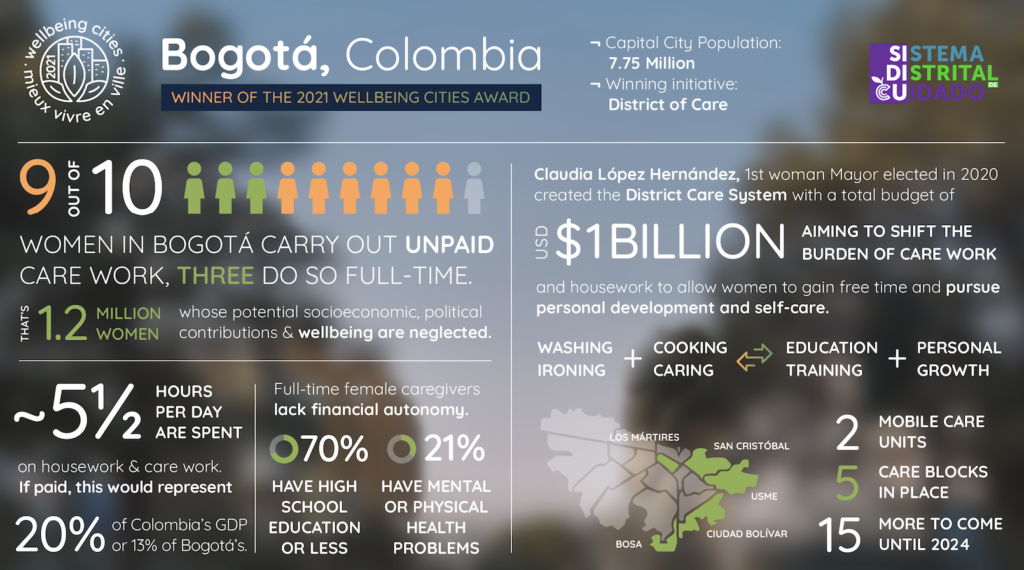

Population: 7.743.955

Mayor: Claudia López Hernández

Language: Spanish

PODCAST

A Conversation with Mayor Claudia López Hernández

Tomos Lewis sat down with Mayor Claudia López Hernández to discuss the initiative and how she’s working towards her goal to make Bogotá a more inclusive and equitable city for all. Listen to threesixtyCITY on all major streaming platforms.

FEATURED ARTICLES

EN | ES The De-feminization of Poverty: the Secretary for Social Integration’s Big Bet

by Xinia Rocío Navarro Prada

EN District Care System of Bogotá, an Innovative Territorial Public Policy Strategy for Colombia

by Ana Isabel Arenas

EN The District Care System: A model of Decent Work and Gender Equality in Bogotá

by Bibiana Aido Almagro

EN | ES Care and Public Policy: A Strategy for Reducing Gender Gaps in Bogotá

by Diana María Parra

EN | ES Bogotá: Transforming Women’s Unpaid Care Work in Times of the Pandemic

by Diana Rodríguez Franco

EN Democracy Without Household Justice is Not Democracy

by Diego Cancino

EN Who Cares? Bogotá’s Path To Becoming a Caring City

by Javier Peña Duque

EN Public-Private Articulation: Fundamental

in Closing Gender Gaps

by Juliana Bejarano

EN | ES To Recognize, Reduce and Redistribute Care Work: the Commitment to Close Gender Gaps in Bogotá

by Natalia Moreno Salamanca

ABOUT THE INITIATIVE

Bogotá’s District Care System (Sistema Distrital de Cuidado)

Q. What challenge(s) related to wellbeing does your initiative or strategy seek to address?

A. The unpaid care burden falls disproportionately on women. With schools closed during the pandemic, this has reached alarming proportions: 30% of Bogotá’s female population now do unpaid caregiving full-time. Two-thirds of them have high school education or less, many have left the workforce, and 21% suffer physical/mental health problems.

Women’s “time poverty” is a structural cause of gender inequality. Full-time female caregivers lack financial autonomy. Ninety percent of them are low-income, and 33% are deprived of time for self-care, which has incalculable impacts on public health. Moreover, this translates to considerable loss of female political participation, the entrenchment of inequality at home and beyond, and lost economic gains for society.

We have designed the Care System to recognize the contribution of caregivers; redistribute responsibility more equitably between women and men; and reduce women’s unpaid care work, so they can pursue personal development and self-care.

Q. How does the initiative respond to the challenge(s) identified?

A. A Care System brought to people’s homes, for persons requiring care and their unpaid female caregivers, which: 1) frees up time for women to pursue self-development (including higher education) and well-being, 2) trains male family members in care work; and 3) addresses gender norms that perpetuate inequality between men and women.

It uses a never-before-tested, “ease-of-access” modality. Care Block locations ensure services can be accessed within a 15-minute walk. For those far from Care Blocks, Care Buses deploy to their community and for those who cannot leave their homes, Door-to-Door Care will bring services home.

The System’s main innovation is its operation: it simultaneously provides professional services for those who require care, while offering educational and leisure opportunities to those who provide care, as well as training men on house chores.

It puts caregivers at the center; organizes the city to meet people’s needs, instead of the other way around; and addresses the inequality of care burden, from a cultural perspective that ensures long-term, sustainable change.

Q. What are some specific examples of the anticipated or observed impacts of your initiative?

Bogotá’s Care System clusters services to respond to the needs in care services in the city. Its targeted population is:

1. Full-time caregivers

2. People who require care: children aged five or less, the elderly and disabled individuals. For caregivers, the system delivers training and leisure activities. For people who require care, the system delivers care services. To date, the System offers more than 30 services distributed in 3 Care Clocks and 2 mobile care units.

The impact measurement framework includes three indicators:

- 1) reduces the time for unpaid care work by female caregivers;

- 2) increases the time contribution by male family members in caregiving within households; and

- 3) more female caregivers receive educational trainings or become gainfully employed and enjoy better mental/physical health.

In the short term, full-time caregivers benefiting from the system will have reduced their care work by five hours per week on average, and will have used it to finish their baccalaureate, pursue a vocational career or take other trainings and well-being activities such as exercise or psychological care.

In the long term, it would be successful if it maintains the previous impacts and generates jobs. According to the Secretary of Finance, investing in care services has a multiplier effect greater than investing in other sectors: every 100 direct jobs created by the Care System results in 79 indirect jobs, while in the construction sector it generates 43.

All this will have a positive impact on one of the city’s main goals: the reduction of female poverty. One out of three women in Bogotá does not have her own income and 20% are unemployed. Time redistribution is a necessary condition for income redistribution.

Q. How did you consider equity & accessibility when designing your initiative? What public-facing participatory tools and approaches have you or do you plan to use throughout the planning, design, and implementation of the initiative?

A. The Secretary for Women, along with two universities, did research on full-time caregivers, which found that 90% are poor or low-income and 33% are single mothers. The Secretary also conducted 21 focus groups, 17 semi-structured interviews and two three-hour sessions with caregivers from diverse populations. They also enabled us to understand how to make a system easily accessible and responsive to their personal needs and home situations.

The Intersectoral Commission of the District Care System has a citizen participation mechanism composed by representatives of the city’s advisory councils (including those of women, children, LGBTI, and city councils on disability, indigenous women and Afro-Colombian women), as well as organizations of female caregivers, to guarantee a differential approach in their design and implementation.

The Commission also invites academia, the private sector and civil society organizations to participate. It also has permanent dialogue with Bogotá’s City Council, which created a special commission for providing checks and balances on the District Care System.

During the design phase of the system, the city administration created a participatory budget platform in which citizens voted in which projects they wanted to invest tax-payer resources to improve their neighborhoods. Citizens prioritized investments in care-related services with nearly 409 initiatives selected city-wide out of a total of 1.321.

Finally, we need the media and influencers to inform, through social networks and digital and print channels, about our services and generate a trend ¡A Cuidar se Aprende! – showing that #CaringIsCool.

Q. How do you or will you ensure your initiative’s long-term, sustained impact? In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, how did you or do you plan to adapt your initiative?

A. As Bogotá’s first female mayor, Lopez pushed for a Development Plan that makes Bogotá a “caring city”, and for this, created the District Care System (with a USD 1 billion budget). The Plan tripled the budget of the Secretary for Women, the entity in charge of implementing the system.

The Care System has also been included in the Public Policy on Women and Gender Equality. Moreover, the upcoming Land Use Plan, which will determine the structural, long-term vision of the city for the next 12 years, incorporated Care Blocks as a new criterion for the city’s urban planning.

The District Care System is in the process of being introduced to Bogotá’s City Council to become a law. It is also a city commitment, not just a government one. The goals and budget assigned for its implementation, including personnel, was approved in 2020 by Bogotá’s City Council as part of the adoption of the City Development Plan 2020-2024 and the city’s annual budget. The legislative body approved it unanimously: the representatives of the different parties across the entire political spectrum voted in favor of the creation and implementation of the District Care System and are continuously monitoring it.

Also, during the COVID-19 pandemic, caregivers continued to receive education and professional training courses by the National Training Service, online and in person following strict biosecurity measures.