How Ordinary People are Crowdfunding Our Cities

mars 28, 2017 — Uncategorized

A Q&A with Spacehive Founder and CEO Chris Gourlay

Large technology companies, family businesses, communities, and individuals alike are now looking to use the city as a medium to achieve larger goals. Creatively using and understanding urban space can help businesses better meet their goals and grow, while also helping democratize urban processes and providing a voice to citizens.

In this Q&A, Chris Gourlay, Founder of Spacehive – the world’s first crowdfunding platform for civic projects and one of the 2016 Global Urban Innovators – shares his thoughts on how to engage and empower crowds to help develop their cities.

What is the potential impact of civic crowdfunding, and how can engaging the public directly improve cities?

Think about cities. They are teeming with ideas, creativity, and resources. There are so many reasons why the citizens and businesses that inhabit them would want to make the civic environment around them better. A new playground means somewhere fun for the kids to enjoy on your doorstep. A beautiful rooftop community garden is your escape from the bustle of the city below.

Yet traditionally we have relied solely on municipalities – sometimes property developers – to provide the sort of streets, sport facilities, greenery and buildings that make us happy and prosperous. We have had no real mechanism allowing ordinary people – the end users of civic space – to come together, propose projects, and help to make things happen.

Civic space is an arena of overlapping interests – citizen, state, business. It belongs to no one and everyone. Civic crowdfunding is a concept that simply acknowledges that reality and seeks to provide an easy way for everyone to come together to create better places.

What we have seen over the last five years whilst we have been designing and testing Spacehive is that there is a huge, untapped appetite for popular involvement in civic improvement. And the traditional players in this space are open to radical change. This is a dynamic that has tremendous potential to reshape the way cities look and feel and to make civic improvement a democratic process.

The irony about all the talk of cuts to public budgets for green spaces, streets, playgrounds and so on is that the lament ignores the resources beyond municipalities’ coffers. Civic crowdfunding is opening people’s minds to re-imagine civic space as an arena that we are all responsible for and can all contribute to, if it suits us to do so.

I believe that over the coming years the simple logic of the model will mean that existing top-down models are replaced with this collaborative approach.

When it does, I think we will see places that are vibrant, richly varied, reflective of local culture, that support strong communities that feel a greater sense of ownership of their environment, and create nimble local economies.

For the citizens behind civic crowdfunding campaigns, how does this process look on-the-ground?

In the case of Spacehive, people come up with an idea, post it on the platform, it’s verified as viable by experts, then they can attract pledges from neighbors, friends, businesses as well as big brands, city halls, foundations, and government funds.

As a backer, you can pledge anything from £2 to £50,000, safe in the knowledge your money will only be taken if the project is successfully funded.

Once an idea is funded, the project delivery manager is responsible for making it happen – sometimes with support from city hall – and it is then ready for the community to enjoy. We also monitor the impact of projects and share data with backers so they can see the difference it has made.

What social impacts can result from the crowdsourcing of civic projects?

They are rich and varied. The projects themselves generate a huge range of environmental impacts: creating green space, restoring buildings, creating new public space, nurturing habitats, restoring heritage, creating new facilities to play sport and so on. Millions of people use or visit them. But projects also impact their creators – running a civic crowdfunding campaign gives people a tremendous range of skills, from marketing and project management to budgeting. We’ve seen people that have done Spacehive projects go on to become real leaders in their community.

Projects impact the wider community as well: communities that back projects say they feel more proud of their area. The economy can also benefit from increased foot traffic or the improved appeal of a place as people are drawn to the area, while citizens feel more empowered to change things locally.

We monitor all these impacts on Spacehive, but they have also been studied in some fascinating reports by the likes of the Mayor of London and Future Cities Catapult.

As cities like London continue to grow, can civic crowdsourcing restore public trust in municipal institutions?

There is a growing, general frustration with democratic processes in the West. At a local level and in relation to planning, there is the sense that people don’t have a meaningful way to participate in the conversation about what places should be.

Public consultations, town hall meetings, petitions, council elections… these mechanisms often feel rather contrived – and as a citizen you can often only react to proposals. Citizens want tangible, meaningful, enjoyable ways to shape their neighborhood, where their act of engagement delivers results.

Civic crowdfunding provides that – you pledge; you get; you enjoy. I don’t think it’s a panacea but, at local level, it does have the potential to provide a new standard of democratic, participatory engagement, where change is led by crowds of citizens and supported by the state and other stakeholders. Many of the councils we work with fully understand that side of civic crowdfunding and see it as an exciting benefit. And I think it’s one reason why the model has attracted so much interest and praise from politicians, including the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Theresa May.

Will existing stakeholders such as mayors, developers, and planners embrace this form of civic participation? What value can it add and which problems could it solve?

It’s a win-win for mayors, developers and planners. Civic crowdfunding creates a neutral space where bold new ideas for places can be market-tested directly with the communities that stand to benefit from them before any money changes hands. Delivering projects becomes more economical – because each pound spent as a municipality, for example, is leveraged 250% on average. But it is also politically and culturally appealing – it unleashes a lot of creativity, energy, goodwill and excitement which you can nurture, steer, and reward. At the end of the day that’s a dynamic people want to get behind and be part of – whether you are a politician, brand or property developer.

What are the most interesting examples of crowdsourced and crowdfunded urban projects?

An impressive example is the Peckham Coal Line: a really imaginative idea by a couple of local people living in Peckham, South London. They saw a derelict railway line which runs between two high streets in the heart of what is quite a densely-built neighbourhood and thought “wouldn’t it be amazing if that was a park meandering through Peckham’s rooftops?”

This local group crowdfunded the feasibility study on Spacehive for £76,000 and the idea captured people’s imagination. They got hundreds of pledges from local people and businesses. Everyone wanted to volunteer their time to help. The local press got excited. A local beer was renamed after the project. And they ended up attracting pledges from the local Borough – Southwark Council – and the Mayor of London. So an incredibly eclectic mix of funders that came together quickly in response to a good idea. The project is now moving ahead to become a reality.

So what you saw was a couple of people who spotted an opportunity to do something for the area that would improve people’s quality of life, help the economy, and played into an aspirational narrative for where the neighbourhood was going. When the community voted for it with their wallets, businesses and the state stepped in to help with the heavy lifting.

For me, this illustrates how civic crowdfunding can unlock exciting ideas and give them a leg up. It’s like providing startup capital for local places.

Most of us would agree that local character and vibrancy are some of the most important elements that define healthy and successful communities.

What are the greatest impediments to crowdfunding becoming a more commonly used tool for enhancing civic spaces and neighbourhood development? What are the risks?

Designing the digital tools to support civic crowdfunding at scale has been a tremendous challenge – it’s not easy to get the mayor to pledge alongside citizens for a host of reasons, nor is it easy to determine whether citizen’s ideas are viable. There is no API you can call to check whether a civic project is good to go. At Spacehive, we have now figured out solutions to most of these challenges by working closely with our amazing partners. But there are more challenges to overcome before this becomes the new normal way of making the fabric of communities.

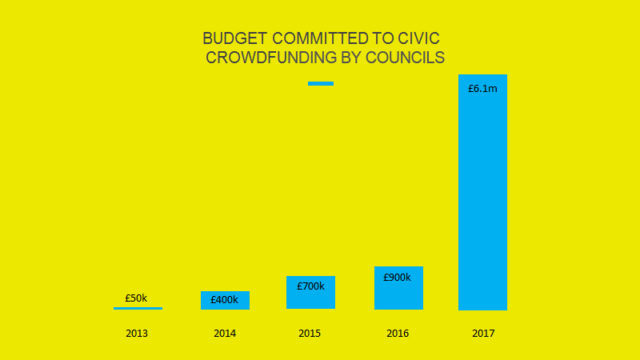

I believe it will, and that it is just a matter of time before the technical, process and cultural challenges melt away. Already 10% of municipalities in the UK have embraced civic crowdfunding and more join every month. More and more brands, foundations and property developers are getting behind it. We are making huge strides towards democratising civic improvement together and I think that process will accelerate over the coming months and years as the benefits are increasingly understood.