Vibrant and Livable – Creating a City from Scratch

September 25, 2018 — The Big Picture

How can you create a sustainable, vibrant and livable city from scratch? This is a question my team at Sweco and I had to answer in 2016 when asked to develop the Masterplan for one of Sri Lanka’s largest and most controversial urban development projects – the Port City. With our urban planning experience and global project references on large scale development globally, we came into the project after the earlier Masterplan proposals had been scraped and the client wanted a completely new proposal.

The new city district was to become home for approximately 60,000 to 90,000 residents and provide a new central business district for Colombo, along with public service, a new marina, tourist facilities and leisure for 170,000 to 250,000 estimated transient population. Some parameters, like the shape and size of the land was already defined from the start. 2.78 square kilometers was to be reclaimed from the sea, expanding the area of existing Colombo City by 7 percent.

You could imagine designing a city on completely new reclaimed land, would be like starting with blank paper. But on the contrary, the location, context, local climate and culture coupled with strong sustainability principles drove the design process during the two-years we were developing the Masterplan.

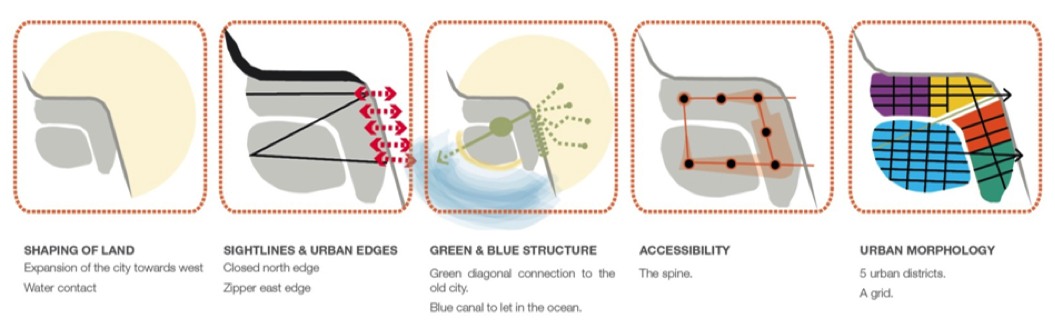

We started out by defining what kind of city we wanted to create and developed the key issues and objectives to guide our work. The new city should relate to the existing old town of Colombo to the East, the Indian Ocean to the West, and the industrial harbor to the North. It should be built upon sustainable public transportation, be walkable and well adapted to the tropical climate. Using the SymbioCity Methodology for sustainable urban development the key issues identified by a multidisciplinary team were used as criteria to evaluate different scenarios at an early stage of the project. The most appropriate options were developed, regularly testing the masterplan against our objectives.

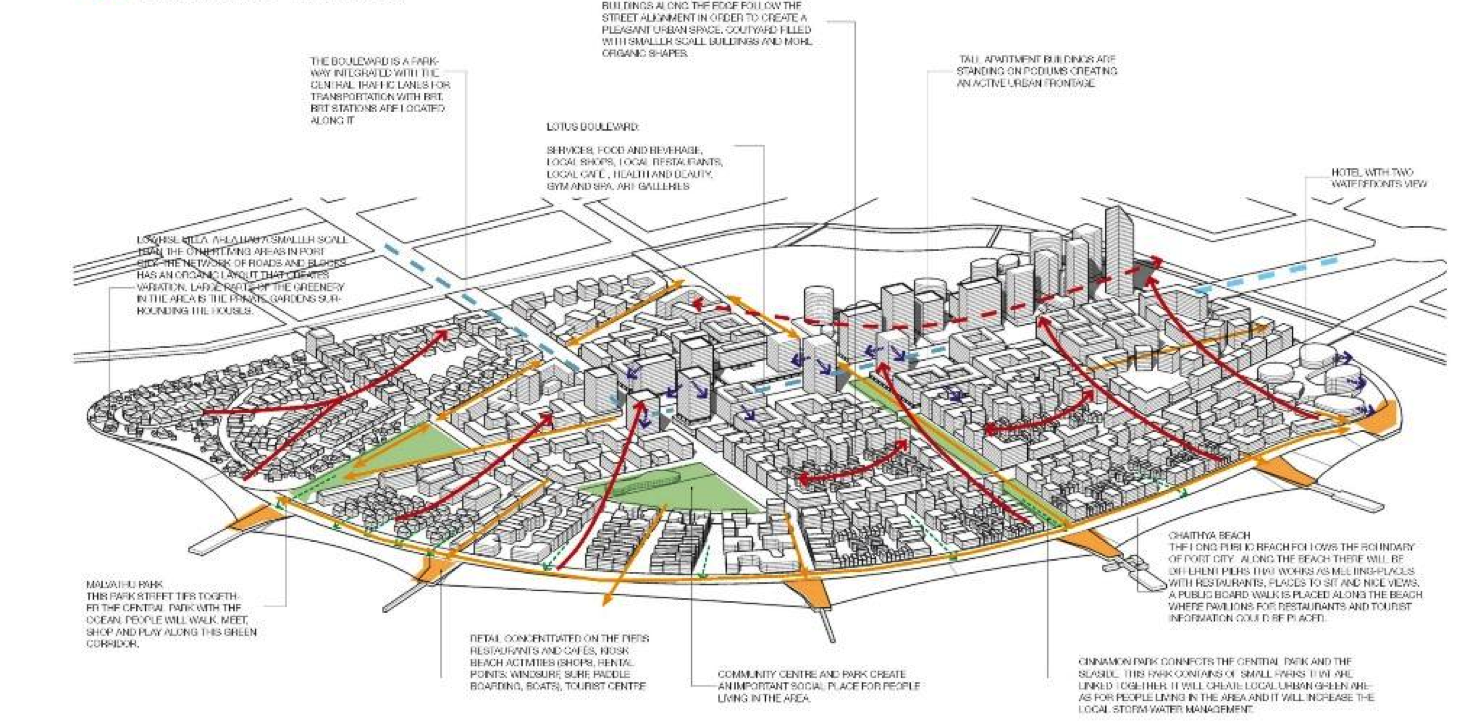

One of the key issues clearly prioritized from the start was transportation and how to reduce car dependency. The development is situated in the center of Colombo which was already severely congested by traffic. A key driver was to create an efficient and accessible public transit system that could redefine the model split of Colombo into a more walkable, bike friendly and public transit driven development. To encourage pedestrian movement in tropical climate, the traditional Sri Lankan and Colombo’s old city architecture inspired an arcade system along important streets, providing a network of shaded pedestrian areas.

Investigating through 3D models how to maximize sea breeze in the urban structure, along with appropriate street section profiles and vegetation was integrated into the design process to create a better urban microclimate. The rectangular shape and orientation of blocks is also a result of passive adaptation measures to reduce cooling demand of buildings.

The mixed-use structure has a centrally located ‘spine’ along a boulevard connecting urban nodes; it is the foundation that supports the development of sustainable transit modes, prioritizing walking, bicycling and public transportation. A prioritized bus rapid transit system (in the future possible to convert to light rail) in the center of the boulevard, functions as the backbone of the city, linking it to the regional public transport network.

One of the advantages of designing a city from scratch is actually the freedom to adapt the land use and form of the city, creating higher density around the transport nodes making the development a clear example of transit oriented development (TOD).

A city district build during a short period of time lacks the natural variation and diversity of cities that have grown over a long period of time. Therefore, we specifically emphasize developing a well-balanced relationship between the public, semi-public and private realms, where spatial diversity, human-scaled environment and complexity is emphasized. Isolated urban “islands” and gated communities are avoided in favor of a continuous urban texture of smaller blocks and free movement through interlinked public spaces.

The green structure intersects the whole city with spaces for ecosystem services such as storm water and flood management, leisure, pedestrian and bike transportation as an integrated part of the system. The reclamation reduced roughly one kilometer of Colombo existing waterfront. At the same time as it has created 5.7 kilometers of new public waterfront, including 1.5 kilometers of beach. Great emphasis was put on the design of public space including parks, street design, squares and waterfronts, making the new district an accessible asset for all citizens of Colombo.

We believe that Swecos largest contribution to the new district has been to create a robust framework built on major sustainability issues through its physical and functional structure in combination with integrated systems solutions. This was accomplished through a transparent and inclusive multidisciplinary design process where the key issues and principles are actively used to iterate the creation of the Masterplan. In a project this complex and long-term it is our hope is that strong principles and priorities with a flexible framework will follow the project and succeed in the overarching goal of implementing a mixed use livable and accessible city adapted to Sri Lankan climate and culture.

Featured photo: © Sweco