What “Smart” Trip Planners Tell Us About What Used to Be “Smart”

July 16, 2018 — Blog

Each of us has diverse preferences, needs and requirements when navigating and moving through the city’s built environment. We each mobilize differently. Mobility (unlike transport) is personal; it’s a joint expression of individual likes and individual ability to move in real time, through physical space, within diverse environments.

The ‘new smart’

As the new U.S. urban agenda prioritizes sustainability, cities increasingly incentivize individuals to choose non-motorized mobility to perform all or most daily activities (or in many cases, penalize individuals for using their vehicle). We are told that the ‘smart’ choice is the non-motorized choice.

If that’s the case, then it is crucial to truly understand how our local communities, the infrastructure they do or do not provide, and the information technology to support our decision-making process all determine an individual’s non-motorized reach. What amenities and services are accessible to me, my connectivity to different modes of travel and ultimately the feasibility of my full community engagement locally is predicated on how my built environment and my navigation technology supports my personal non-motorized mobility.

While it has previously been mostly true for people with disabilities and the aging population, the ‘new smart city’ will increasingly create a dependency between non-motorized mobility and tangible outcomes in quality of life and social participation. So the ‘new smart’ dictates that everyone will want to live in a community that maximizes their individual ability to move independently and optimizes their reach locally.

In the not-so-distant-past, ‘smart’ was different

Yet in the U.S. many urban environments were planned with quite a different social norm, one that privileged private vehicle use over public transport and valued the iconic life of a large suburban home, two cars and access to an outbound system of roads and freeways. It is within that same environment that much of our navigation and wayfinding technologies found their roots. Non-governmental mapping, digital mapping, private GPS and navigation technologies were motivated by a lucrative private vehicle market to sustain a consumer culture that glorified the freedom of ‘choosing’ to drive to the mall at the other end of town for a carton of milk and some bread. For similar reasons, intricately detailed, standardized road network data is available throughout much of the U.S., while sidewalk and pedestrian infrastructure data is disparate, non-standardized, decentralized and fails to specify how foot-paths and sidewalks are actually connected (this is the kind of information that is ultimately necessary to offer automated pedestrian trip planning that considers individual mobility).

What does inclusive pedestrian-smart technology look like?

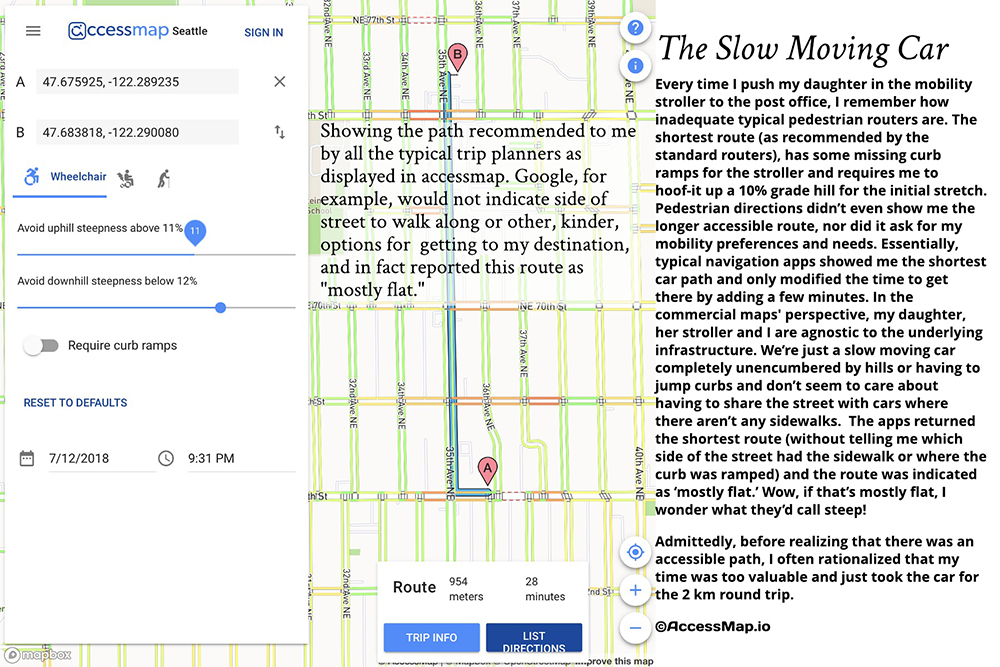

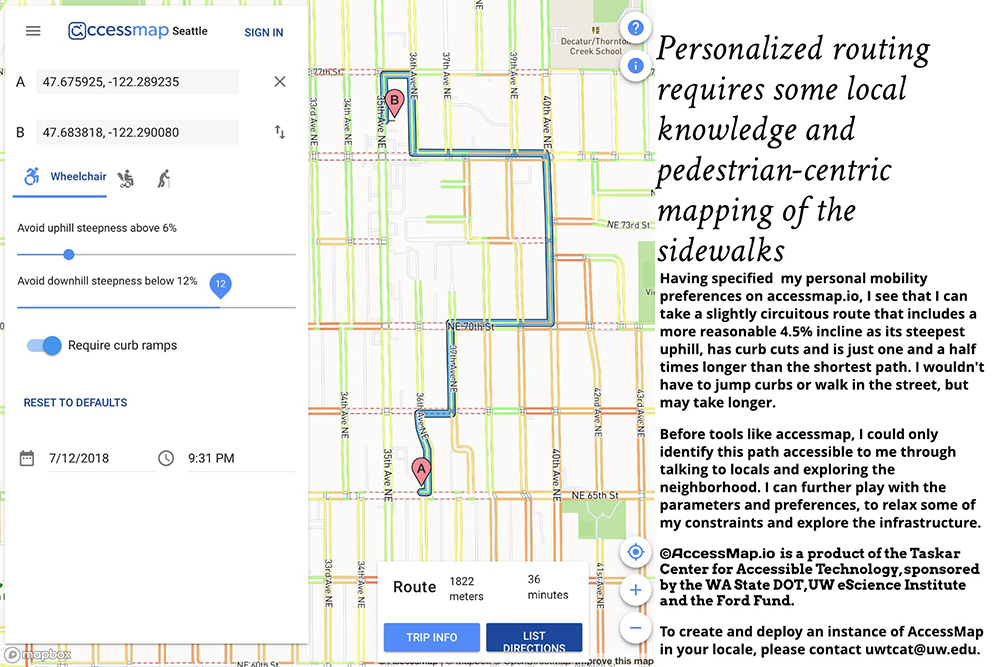

The concern with some of the current smart city developments is that the starting point is a big-data model devoid of place. When Columbus, Ohio won $50M in the 2016 Smart Cities Challenge, Sidewalk Labs (an Alphabet Company) offered to tool the city with a software tool and the associated infrastructure in a product named FLOW: integrating big data with ubiquitous sensing and harnessing the power of crowdsourced mobile data to reduce congestion and tool every traveller with the presumed capacity to make ‘smart’ decisions. FLOW and other products like it assume that a transit model can be forced upon a place or a built environment, and that all pedestrians go about in the same homogeneous way, with no preference between paved and unpaved sidewalks, no regard to elevation change, basically like slow-moving cars.

Our vision at OpenSidewalks is to start with a community of practice and place, and to use technology to understand (both computationally and culturally) the links between mobility and the way spaces are built and configured. OpenSidewalks promotes a pedestrian-centric approach to non-motorized mobility and city planning that starts with inclusion of urban dwellers (and particularly, commuters with diverse mobility profiles) to learn travel patterns and tool travellers with the information to make decisions that are ‘smart’ for them: making the use of pedestrian spaces easier and maximizing their ability to take delight in non-motorized travel.

It is only through positive pedestrian experiences and a sense of place that we can start to address the hard part: the complex social processes of undoing social norms, asking commuters to radically change their mobility and consumption patterns and choose to walk and cycle more.

“Design changes that are needed to accommodate the Convention [on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities] will, over time, generate new ideas and innovations that will improve life for all people.”

The UN on its Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Cover photo © Justin Main